I’ve been thinking a lot about my journey as a reader and, specifically, my journey to become a critical reader of complex text. According to Jennifer Duncan at the University of Toronto,

“Critical reading is a more active way of reading. It is a deeper and more complex engagement with a text. Critical reading is a process of analyzing, interpreting and, sometimes, evaluating. When we read critically, we use our critical thinking skills to question both the text and our own reading of it.”1

I graduated from a large public high school in the 90’s with good grades and a path to college. I knew how to chew up and regurgitate facts quite effectively. I could consume text like nobody’s business. But did I understand it deeply? Did I grapple with its meaning? Not really. Text was one-dimensional to me, printed words on sheets of paper.

My junior year of college, I watched as a peer who had attended an elite private school fervidly swiped her highlighter across the same book that I was staring at passively. I saw her pick up her pen and scribble questions in the margins, noticing how empty and lonely my margins appeared. And I asked her, “What are you doing?” She explained to me, for the first time in my life, the concept of critical reading, and I was forever transformed. Now, for better or worse, I can barely read fiction without a highlighter and a pen! I stopped consuming text and started talking to it, with interest, vigor, and cognitive engagement. And I felt my brain grow in the process.

As a young high school teacher, I presented my students with complex texts: Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, Ronald Takaki’s work, James Baldwin, Paolo Freire, and later, great works of fiction from across the globe. But I didn’t know how to teach my students to become critical readers. Frankly, literacy wasn’t a focus of my credentialing program. We learned how to teach the “content,” not literacy. Only later did I grasp how fundamental critical reading is to success in every discipline, and how inextricably linked to equity.

You see, I could overcome my literacy deficits through the unearned advantages of being white and middle-class. For my students—almost all youth of color from high-poverty communities—there was no free pass on critical reading. This was the gateway skill that would make or break their path to college and produce either a success story or a college persistence statistic.

Over time, I realized that critical reading does more than make us engage with text. It helps us ask questions about text and contextualize what we read in a sociopolitical frame. As I learned to teach my students critical reading skills, they gained access not just to the written word, but to power. They developed critical consciousness as thinkers and participants in the democratization of ideas. If I wanted to disrupt historical patterns of achievement, I needed to teach my students how to read critically.

“I realized that we are asking teachers to teach critical reading, but they are no longer engaging in critical reading themselves. This seemed like a big disconnect that we needed to address.” –Tanya Friedman

Recently, my friend and phenomenal educator Tanya Friedman reflected on her learning from a literacy project she has been working on with New York City teachers: “I realized that we are asking teachers to teach critical reading, but they are no longer engaging in critical reading themselves. This seemed like a big disconnect that we needed to address.” This comment struck me as I thought about how sporadically I prioritize my own reading. Like many of you, life gets consumed by the culture of busy, and one of the first casualties for me is text!

That day, I recommitted to reinvest in my own critical reading. As author adrienne maree brown writes, “What you pay attention to grows.” I wanted to grow, or at least deepen, these neural pathways, and there was only one way to get there. In my next post, I will share what I am currently reading and how critical reading is shaping my recent experiences with text.

What are your thoughts on this topic? If you’re an educator, how do you practice and teach the skill of critical reading?

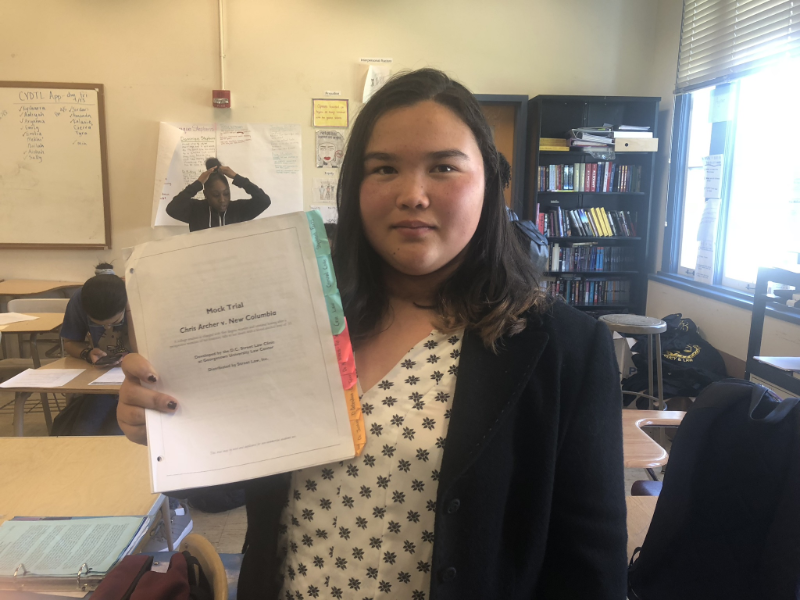

Pictured above: Sally, a student at Oakland Technical High School where I have been helping to design mock trials, uses critical reading to analyze her trial packet.

1 Jennifer Duncan. The Writing Centre, University of Toronto Scarborough. Modified by Michael O’Connor. Handout also available at http://ctl.utsc.utoronto.ca/twc/webresources.

***

Upcoming Events – SAVE THE DATES!

November 13-14: Brave Spaces Institute for Mounds View Public School District (all admin), Minnesota.

February 12-13, 2019: Brave Spaces Institute (Brave Spaces 101), Oakland, CA

Our next 2-day Brave Spaces Institute will be held at the beautiful Lake Temescal Beach House in Oakland, California on February 12-13. One of our recent participants wrote, “I don’t know that I’ve ever attended two days of PD and desperately wanted a third (or fourth!). The intentionality of each part of the two days added such depth to the experience. My mind is buzzing and my heart is filled with hope as I leave to take my learning back to my school community. This workshop really is a gift that all educators should experience.”

February 14, 2019: Facilitation for Liberation (Brave Spaces 301), Oakland, CA

Designed for leaders and educators who have gone through the Brave Spaces Institute, this one-day Brave Spaces 301 will transform your approach to designing and facilitating adult learning spaces through an equity lens.

Please note: In future, Brave Spaces 301 will have Brave Spaces 101 as pre-requisite, but for this pilot session on February 14 ALL are welcome! Take $100 off your registration for Brave Spaces 301 if you register before December 21, 2018.

Registration forms available soon!

Enter your email here and get a free copy of the first chapter of Street Data!

Enter your email here and get a free copy of the first chapter of Street Data!

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.