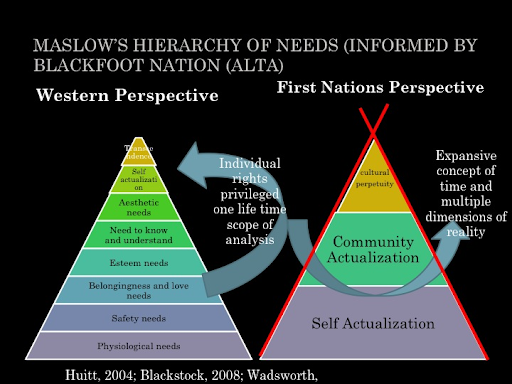

[Source: This slide was presented by University of Alberta professor Cathy Blackstock at the 2014 conference of the National Indian Child Welfare Association. It compares and contrasts Western and First Nations perspectives.]

Thanks to this March 2019 blog by Barbara Bray, I became aware of the legacy behind Maslow’s renowned model—a story of systemic racism, Western epistemology (or ways of knowing), and the forced invisibility of Indigenous knowledge. Let me give you the short version before introducing you to Blackfoot clinical psychologist Deb Pace who schooled me on this history.

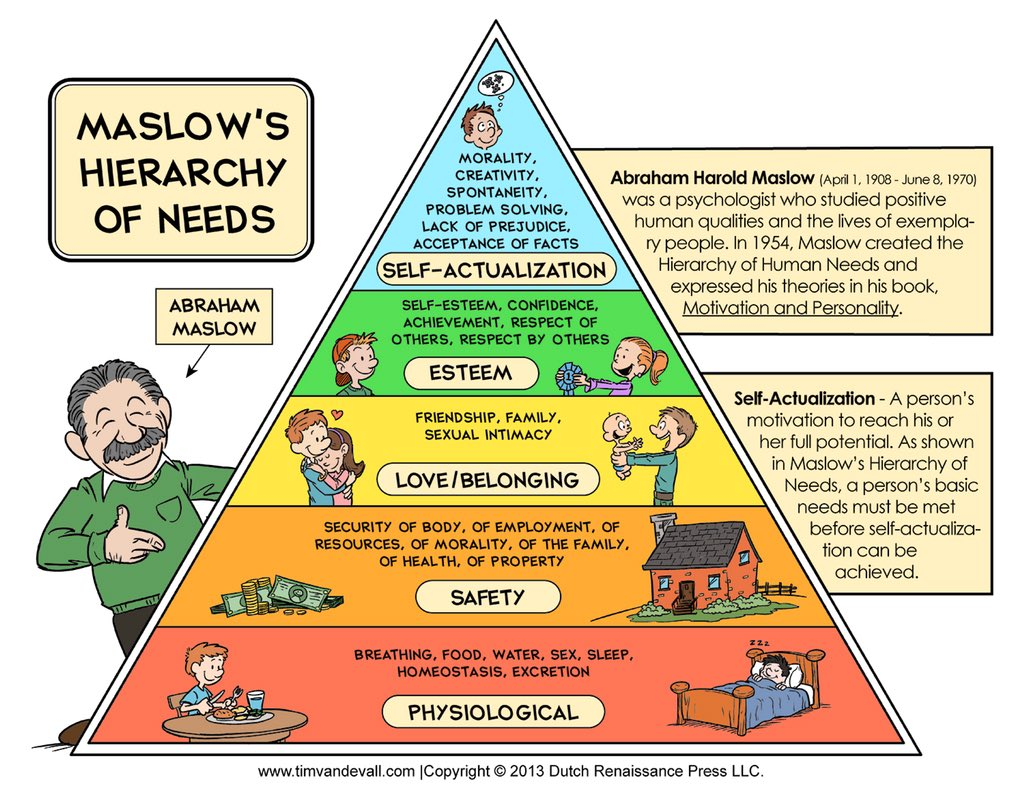

First, study the image below, a typical representation of Maslow’s hierarchy. Notice what you see: a smiling white male “expert” on the left; a description of Maslow as a psychologist who studied “positive human qualities and the lives of exemplary people”; the classic hierarchy beginning with physiological needs and rising to an apex of self–actualization. Notice what you don’t see: any reference to Indigenous peoples, the Blackfoot Nation around whose society Maslow’s model was built, or an expression of values that transcends the individual (aka “self”) to ascend to community or collectivism. Maslow’s hierarchy as typically presented is white-washed, stripped of its roots in Indigenous knowledge, and firmly entrenched in the Western epistemology of individualism. The pinnacle of human development is actualization of self, not community, society, or generational legacy. (In the States, we see the extremity of individualism in the current anti-masking movement, for example—the notion that my individual right to choose not to wear a mask supersedes the community’s right to public health and safety.)

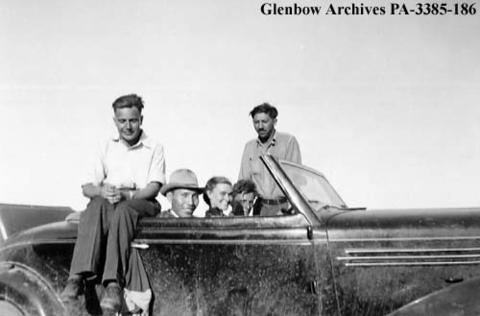

What’s missing here? Well, first of all, the history behind the model! Maslow’s Hierarchy was developed from Maslow’s firsthand observations of the Blackfoot Nation, a highly successful and developed society with which he embedded himself before drafting his theory. Check out the archival photo below of Maslow at the Blackfoot Reserve in Alberta. Maslow was apparently stuck on his theory of human development and went to spend time with the Blackfoot, which greatly influenced his theory. He “borrowed generously” (to put it lightly) “from the Blackfoot people to refine his psychological theory on the hierarchy of needs” (Michel, 2014).

Why don’t we know this? According to Dr. Pace, the American and Canadian governments buried the Blackfoot roots of Maslow’s theory because they didn’t want to elevate a positive narrative about the Blackfoot people. In this excerpt of my interview with Dr. Pace, she talks about elders today who remember Maslow spending time on the reserve as he studied their sophisticated society including a “granny” who said, “Oh, I remember him.” At some point, Dr. Pace encouraged her colleague Dr. Sidney Brown, Behavioral Health Director at Navajo Regional Behavioral Health Center, to write a book on this topic. Dr. Brown went to the Smithsonian archives to find more information and eventually connected with Maslow’s daughter who gave her permission to excavate Maslow’s hidden archival box. There, she found this unsung story and began to unravel it in her own book, Native Self-Actualization: Transformation Beyond Greed (Book Patch, 2014).**

So take a deep breath and take this all in… One of the most popular conceptual models in Western education was built on the wisdom and sophistication of a First Nations society, which was then made completely invisible in the literature. This is not to disparage Maslow or suggest that his model lacks value. There is certainly merit in thinking about a hierarchy of needs as we aim to support students, and particularly ensuring that our institutions attend to foundational physiological and safety needs.

However, to erase the Blackfoot influence on this theory is to support systemic racism and white supremacy, whether unconsciously or not. Beyond the historical invisibility, there’s the fact that Maslow’s hierarchy distorts and inverts the point of the Blackfoot worldview. You’ll note that self-actualization is the base of the First Nations tipi (not a hierarchy, by the way… we’ll talk about the symbolism of the tipi in my next blog, which will include interviews with Blackfoot elders), not the peak. After “self” comes community, which is the purpose of becoming an actualized human being—to be of service to our communities as independent webs of humanity. And above community, reaching toward the expansiveness of the sky, lies cultural perpetuity, or the idea of sustaining cultural values across space, time, and generations.

This entire story took my breath away when I learned it. It made me first angry, then sad, and finally determined to be a co-conspirator in the long arc of educational justice by helping to unmask these types of histories. Stay tuned for the next piece where we hear from elders around what it means to center and uplift Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and learning in these troubling times.

What are your thoughts on this story? Had you heard it before? What do you wonder as you read this?

**Note: Support Indigenous authors by following Dr. Brown’s advice on her Linked In page! “Thank you to everyone for the continuous encouragement and support offered through this journey. The elders say we all come here for a reason. We agreed to do our life work before we arrived. We are here to give back. The book presents all my elders native teachers. I made their knowledge my life work. The book represents the help each offered along the way. The story tellers, the wisdom, the practices and knowledge of so many tribes freely shared so we can help the people of all nations. The book addendum presents to previously unpublished papers by Abraham Maslow on the Blackfoot People. The book was published November 2014 and available at thebookpatch.com $20 plus shipping and handling fees. Contact me for bulk purchases. Sidney Stone Brown Psy.D.”

In other news…

- My book Street Data: A Next-Generational Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation, with my dear colleague Dr. Jamila Dugan, is done! It’s in full publication mode now and will be in your hands in March 2021. Keep in touch for information on pre-ordering.

References

Blackstock, C. (2011). The Emergence of the Breath of Life Theory. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 8(1). White Hat Communications.

Brown, S. S. (2014). Native Self-Actualization: Transformation Beyond Greed. BookPatch.

Bray, B. (2019, March 10). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs. Retrieved from https://barbarabray.net/2019/03/10/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-and-blackfoot-nation-beliefs/

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

Michel, K.L. (2014, April 19). Maslow’s Hierarchy Connected to Blackfoot Beliefs. Retrieved from https://lincolnmichel.wordpress.com/2014/04/19/maslows-hierarchy-connected-to-blackfoot-beliefs/.

Enter your email here and get a free copy of the first chapter of Street Data!

Enter your email here and get a free copy of the first chapter of Street Data!

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.